The fight that never was

A fight between Bombardier Billy Wells, British heavyweight champion and American Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion of the world, was scheduled for Earl’s Court exhibition centre, London on 2 October 1911.

Jack Johnson

American Jack Johnson, the ‘Galveston Giant’, was the first black heavyweight boxing champion of the world. This was at a time of virulent and open racism, of the popular, institutional and legal kinds. In a documentary about his life (‘Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson’, companion to the 2004 biography of the same name by Geoffrey C. Ward), American filmmaker Ken Burns opined that:

For more than thirteen years, Jack Johnson was the most famous and the most notorious African-American on Earth.

Johnson won the title in 1908, defeating the Canadian Tommy Burns in Sydney, Australia. Johnson’s victory over ex-champion Jim Jeffries, who came out of retirement especially for the fight in Nevada in 1910, led to anti-black riots throughout America resulting in deaths and injuries.

'Bombardier' Billy Wells

‘Bombardier’ Billy Wells was British heavyweight champion. William Thomas Wells was born on 31 August 1887 and baptised on 25 September 1887 at St George in the East. His baptism record and school admission record (at Broad Street School on 9 January 1899) are held at The London Archives.

His nickname was a reference to his previous rank in the British Army, in which he served from 1906 to 1910 (he re-enlisted during the First World War, then attaining the rank of sergeant).

A storm of protest

A fight between Johnson, the reigning world champion, and Wells was scheduled for the Earl’s Court exhibition centre in London on 2 October 1911. News of this generated a storm of protest, motivated by a mixture of religious opposition to the perceived immoralities of prize-fighting and gambling on the one hand, and overt racism on the other, with an opposition to contests between the races.

Reverend Frederick Brotherton

The key figure in the campaign of opposition was the Reverend Frederick Brotherton Meyer, an important Baptist minister. Meyer organised a petition requesting that the Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, ban the proposed match 'on the grounds of public order'. The ‘Sporting Life’ newspaper indicated that Churchill believed that “what is contemplated is illegal” (26 September). The campaign was also supported by, amongst others, the Archbishop of Canterbury and other bishops, university heads, Boy Scout founder General Baden Powell, Field Marshall Lord Roberts, and Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald.

What is contemplated is illegal

The Home Office declared that the fight would be ‘illegal’, and so the promoter, Wells and Johnson, and their managers, were served with an injunction by the Director of Public Prosecutions and had to prove that there would not be any breach of the peace if the match went ahead. Johnson was served with his injunction at the Royal Forest Hotel in Chingford where he was staying for his Epping Forest training camp.

Bow Street Police Court

A hearing was held at Bow Street Police Court on 28 September 1911 and a huge crowd turned up. Johnson chose to defend himself, rather than hire legal representation, and he skilfully cross-examined the police witness himself. A court register (PS/BOW/A/02/002) is held at The London Archives for that date.

It records that John A Johnson and William Thomas Wells, 'Contemplate a breach of the peace & to find sureties to keep same'. Also in the dock were the promoter James White and the managers James Maloney and Robert Claud Jenkins who 'aid and abet above & to find sureties to keep peace'. The Minute of Adjudication for each of the five reads 'Adjourned sine die'.

Unfortunately this entry conveys none of the drama of the day’s proceedings. For that one must turn to newspaper coverage. It transpired that on the same day, the High Court granted an injunction applied for by the owners of the freehold of the land on which Earls Court stood (the Metropolitan District Railway Company). This was to prohibit the lessees of their property (Earl’s Court Company) from hosting the fight. Faced with that White, the promoter, backed down; all the parties were bound over to keep the peace; and Wells promised never to meet Johnson in a boxing match anywhere in the United Kingdom or the Empire. With this the Home Office dropped the case.

London County Council Theatre and Music Hall Committee

Another strand of the campaign to prevent the fight was to target the venue itself. In this regard the Committee Presented Papers of the London County Council (LCC) Theatres and Music Halls Committee for 11 October 1911 (LCC/MIN/10951) make fascinating reading.

There is a substantial bundle of correspondence; letters and resolutions of protest against the fight taking place and calling for it to be prevented, or if it did go ahead for the Earl’s Court venue to be refused a renewal of its license. There was an orchestrated campaign by a variety of Non-Conformist church organisations throughout the country against the fight.

The brutality of boxing

Almost all of the correspondence emanates from such quarters and the language is strikingly similar throughout them, suggesting maybe the use of some sort of template or pro-forma. The bulk of the written objections are couched in terms of the brutality of boxing, its immorality, the 'demoralisation of our youth', and the associated evil of gambling. Some also explicitly raise the racial aspect, positing that such a fight would 'intensify racial difficulties throughout the Empire', or would 'tend to aggravate the colour feeling where it already exists'. One particularly hyperbolic example from the Calvary Welsh Baptist Chapel Church and Congregation frets that it could result in:

revolutionising our Empire, and justly bring down upon the Wrath of Heaven.

Typical in the records, is this resolution accompanying a letter dated 19 September 1911, and received by the LCC on 21 September 1911:

That this meeting of the Woolwich Tabernacle Brotherhood hereby protests against the so-called 'Boxing Contest' which has been arranged to take place at Earl’s Court on October 2nd, believing that such an exhibition must exercise a baneful influence both upon those who take part in it and upon those who witness it. The reproduction of the details by means of the Cinematograph will extend that deleterious influence especially among the Young in all parts of the World. We, therefore, appeal to His Majesty’s Government, to the Home Secretary and to the London County Council to prohibit this degrading spectacle.

Cinematograph reproduction

Opponents of the fight were also concerned about 'the cinematograph reproduction of exhibitions so degrading and demoralising in character'. Indeed, the previous year the LCC, on 10 July 1910, had warned theatres against exhibiting the film of Johnson’s victory over Jeffries on the grounds that it was 'undesirable'.

The Signed Minutes of the Theatres and Music Halls Committee (LCC/MIN/10732, p799) has the following under minute four:

The Chairman referred to the arrangements made in connection with a boxing contest between Jack Johnson and Bombardier Wells, which it was proposed should take place on 2nd October, in the Empress Hall at Earl’s Court Exhibition, and to the fact that the exit arrangements were not considered satisfactory and that the plans submitted were accordingly disapproved by him. RESOLVED - That the disapproval of the drawings submitted with regard to the arrangements proposed to have been made in connection with the contest to be reported to the Council.

There is a lone letter in the bundle opposing this point of view. W. Lawler Wilson, protesting against the LCC intervention to prevent the contest taking place wrote:

I am afraid this reason [alluding to the Johnson-Jeffries fight in America, and what happened around that] for attempting to prevent a perfectly legal proceeding is not a very satisfactory one. The “disgust” you refer to was not felt or expressed by the majority of genuine sportsmen. Had Jeffries beaten Johnson there would have been great enthusiasm, and no disgust. But the fact that the negro was victorious was sufficient to call forth one of the most unworthy exhibitions of race prejudice I have known. May I inform you that I have seen negro boxers beaten by white men again and again in this country, and that never once have I heard any protest raised.

Jeffrey Green, in an essay 'Boxing and the ‘Colour Question’ in Edwardian Britain: the ‘White Problem’ of 1911', argues:

Boxing had an uncertain status in Britain. In November 1911 a match between Jim Driscoll and Owen Moran scheduled for Birmingham before 10,000 forced the National Sporting Club to employ a fine lawyer to defend the pair and the promoter, but he was unable to show cause why they should not be bound over to keep the peace - and the match was cancelled. Such an undertaking was an enormous risk for the promoters who would face fines and even imprisonment if disturbances occurred. In view of the Driscoll and Moran decision, it seems safe to say that if Jack Johnson had been white, the legal and financial reasons behind the ban on his fight with Wells would have been enough. Those who added “race” to the mixture exposed their bigotry then and now. That addition was “deplorable” as the Church Times had said, and as The Times noted “the large number of contests between white and black men and [that] there had never been an attempt to get a licence of the premises where they were to be held revoked as a consequence.

The fight never took place

So, the fight never took place. Johnson was a larger-than-life, flamboyant, controversial, and complex character. His penchant for fast cars, diamonds and his serial ‘liaisons’ with women, especially white women, further raised the ire of racist whites both in America and beyond. He remained a figure in the popular imagination, even in Britain. British 'Tommies' referred to German shells in the First World War as 'Jack Johnsons', presumably a reference to their colour, speed, and power.

Convicted by an all-white jury

Persecuted by the authorities, in 1913 he was convicted by an all-white jury for violating a Jim Crow law (the Mann Act) that made it illegal to transport white women across state lines for 'immoral purposes.' He was sentenced to a year in prison, but skipped bail, fled the country, and lived in exile in a series of countries in Europe and Latin America as a fugitive. He lost his title in 1915 to Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba. He returned in September 1920 and spent 10 months in jail; the conviction effectively destroyed his career and his life.

A posthumous pardon for Johnson

There was a long-running campaign by his relatives and supporters, including celebrities and leading United States politicians, calling for a posthumous pardon. This was finally successful in May 2018 when President Donald Trump signed one at a ceremony in the Oval Office at the White House. This was attended by, amongst others, a then world heavyweight champion - Deontay Wilder, a former world heavyweight champion - Lennox Lewis, and the actor/director Sylvester ‘Rocky’ Stallone.

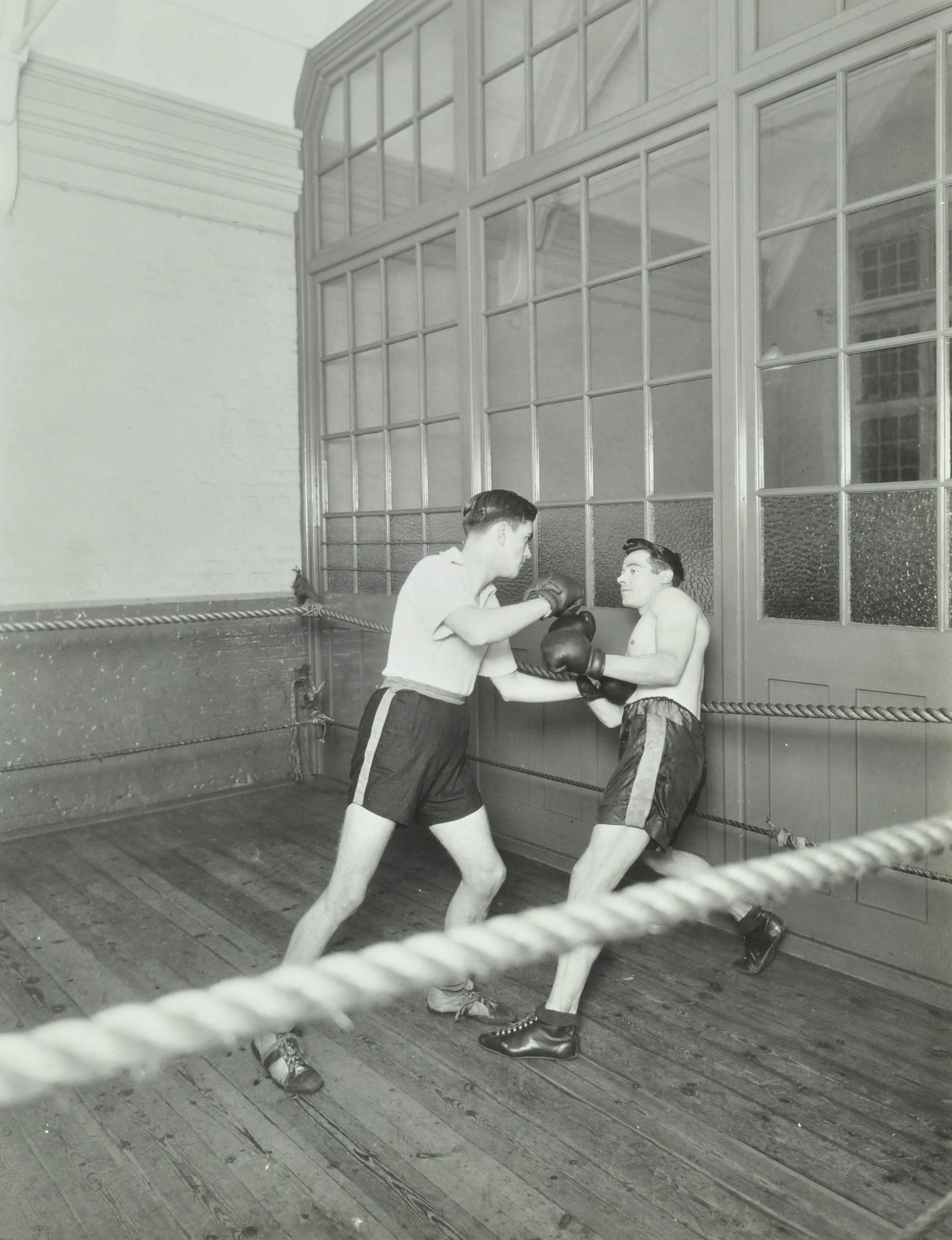

The fights of Billy Wells

'Bombardier' Billy Wells was the British and British Empire Champion from 1911 until 1919, defending his title fourteen times. We also have a contract between Crystal Palace Trustees and the International Boxing Promoting Syndicate for a contest on 27 May 1922 between Wells and Frank Goddard (CPT/057). His last fight was in 1925. He later became known as one of the Rank gong men, the muscular figure seen striking the gong in the introduction to J. Arthur Rank films.

The Lonsdale Belt that Wells won was the original heavyweight belt and was crafted from 22 carat gold unlike later belts. The belt was kept at the Royal Artillery Barracks in Woolwich, South East London, but is now at Larkhill in Salisbury following the move of the home of the Royal Artillery.

A 'colour bar'

A 'colour bar' (that prevented any non-white boxers from fighting for championships) remained in British boxing until 1947.

Want to see the documents mentioned in this article?

You can investigate the records mentioned in this article by first registering for a History Card. Take a note of the references and then you can request them via our catalogue.

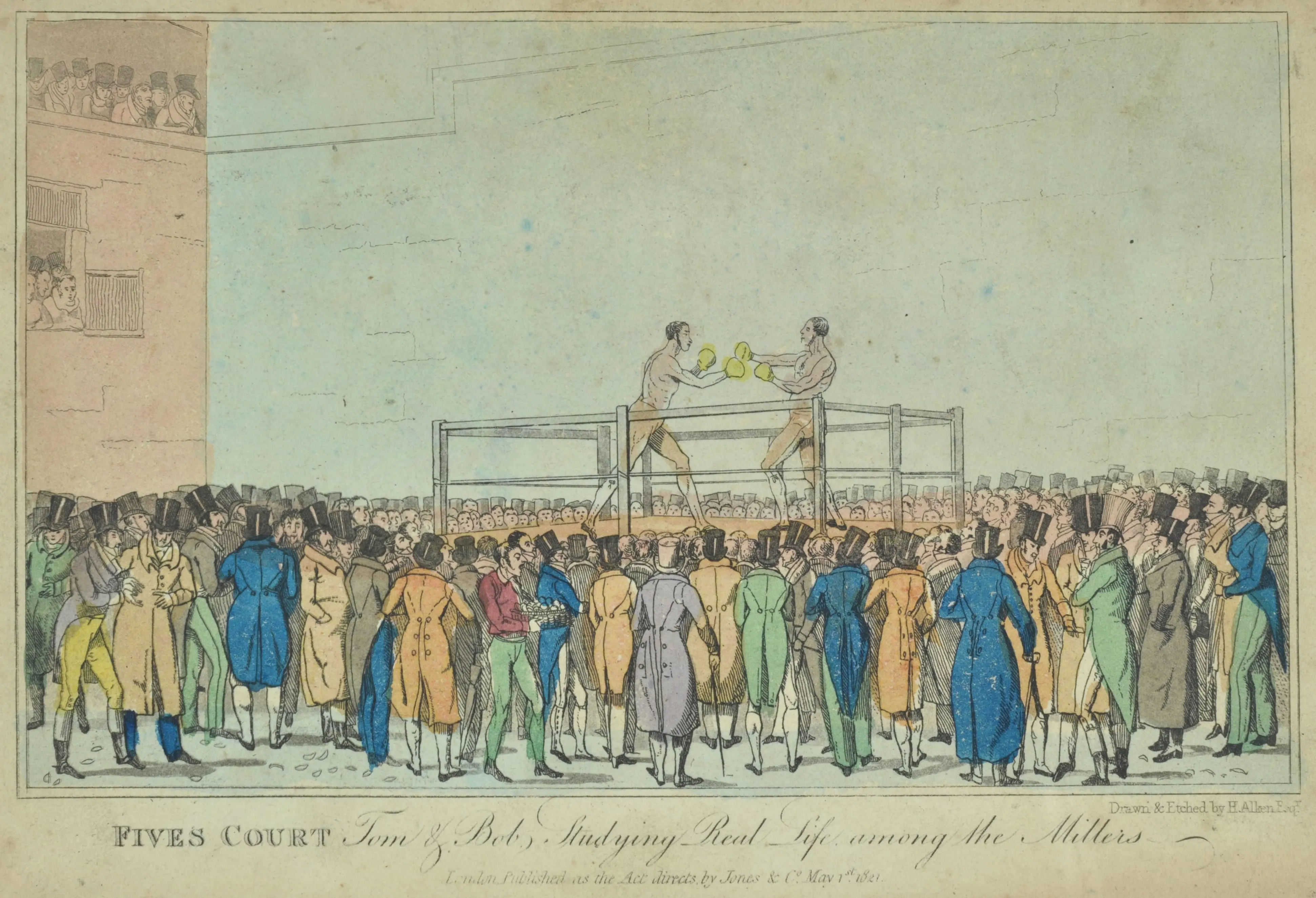

RegistrationThe London Picture Archive

Want more? Why not check out our gallery on the London Picture Archive that looks at the history of boxing in London.

Boxing London Gallery