Victorian Workhouse Diets

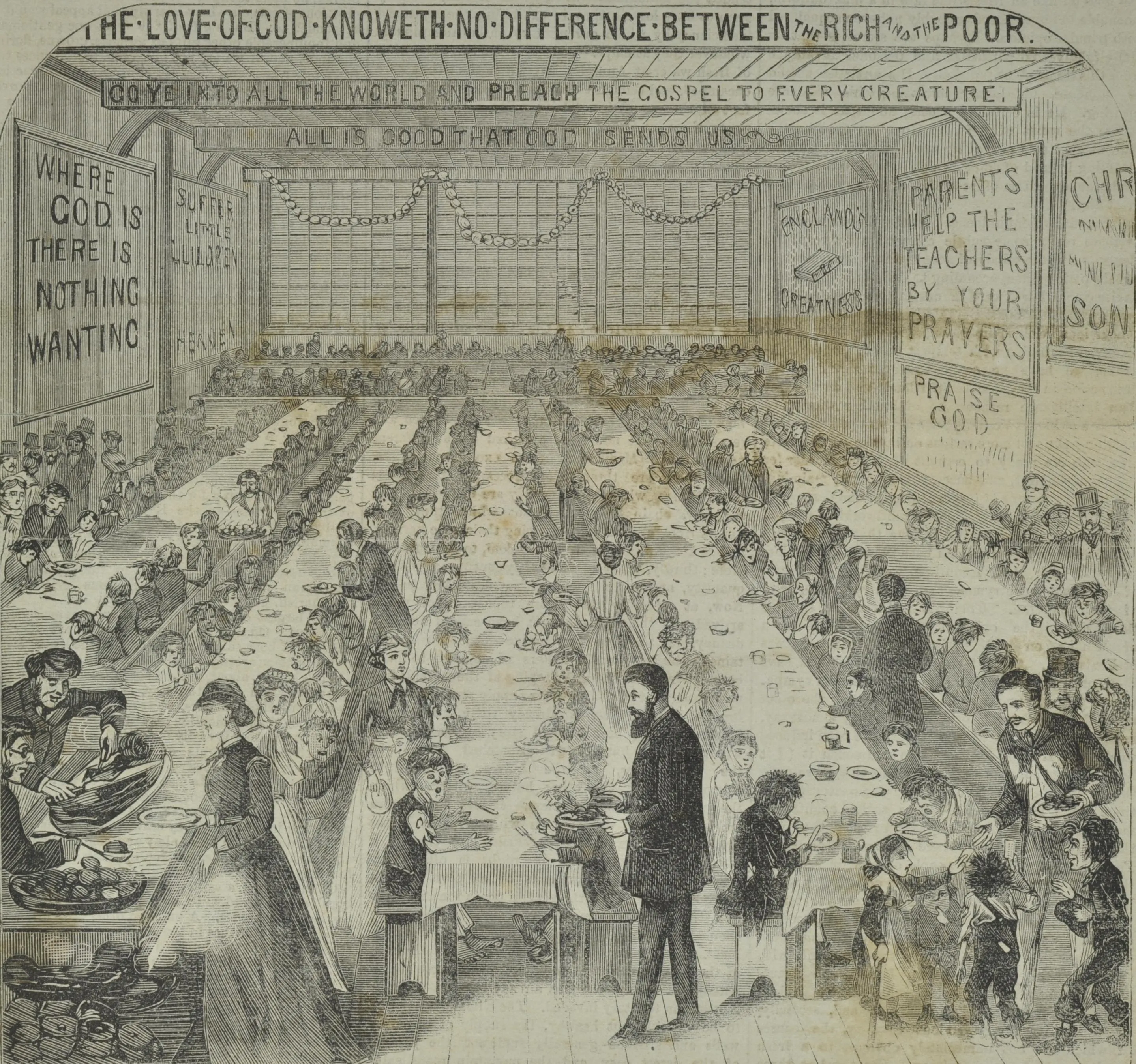

Following the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, workhouse diets were deliberately inferior to the diet of the labouring classes – a measure the Poor Law Commission believed discouraged the exploitation of poor relief. Limiting diet compounded an already distressing situation for the destitute, who had no option but to enter the feared institutions, helping to place them firmly at the bottom of society.

Diets in the Victorian Workhouse

on no account must the dietary of the workhouse be superior or equal to the ordinary mode of subsistence of the labouring classes of the neighbourhood.

To enforce these diets, the Commission issued six example dietary charts. Each Board of Guardians then adopted a chart within their Union workhouse. Harbouring a belief in quantity over quality, the workhouse diet’s main component was bread. The 1838 dietary chart, having been adapted from the example charts, for the West London Union provides all inmates 12 ounces per day.

In a dietary table for male and female adults from 1838 the following advice is given:

Aged and Infirm - Women above sixty years of age to be allowed 1 ounce of tea and 6 ounces of sugar per week at the direction of the Guardians. Children - under nine years of age to be dieted at discretion above nine to be allowed the same quantities as women. The Diet of the Sick - to be in all cases subject to the control of the Medical Officer.

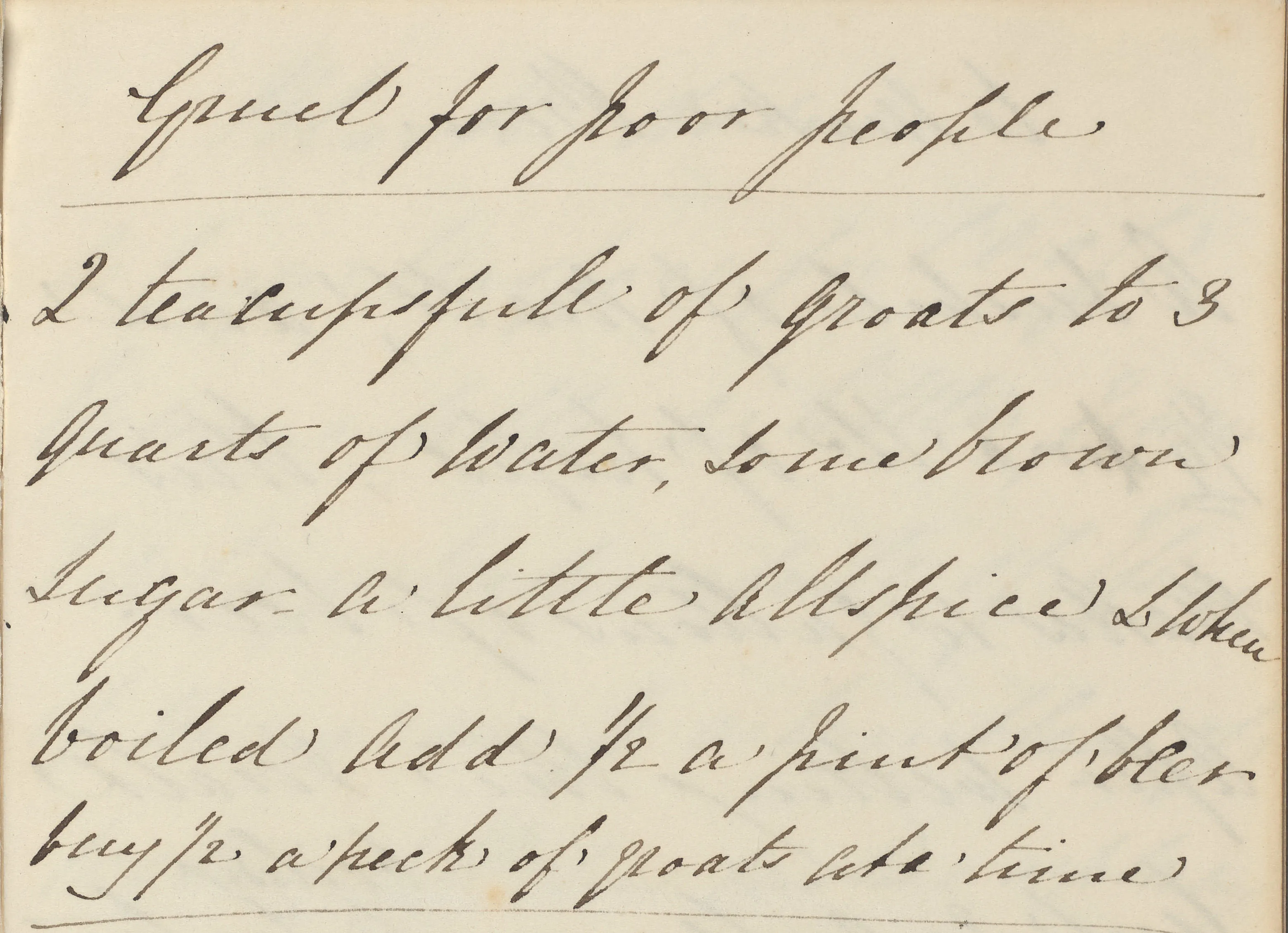

Gruel or porridge was another staple, a contemporary recipe for which we have in our collections. There has been much debate about the ‘adequacy’ of the workhouse diets, often questioning Dickensian views of the workhouse, with L Smith suggesting:

Given the limited number of food staples used, the workhouse diet was certainly dreary, but it was adequate.

Gruel for poor people: 2 teacups full of groats to 3 quarts of water, & ounce brown sugar, a little allspice & when boiled add 1/2 a pint of beer, buy 1/2 a peck of groats at a time.

An 'Adequate' Diet?

Viewing workhouse diets as ‘adequate’ assumes that recommended dietary charts were adhered to, despite evidence to the contrary. The Boards of Guardians had the power to restrict the diet of inmates who committed “refractory” behaviour, including swearing, refusal to work, and not washing to name a few.

The Commissioners, by 1837, felt the need to police this power to make sure that inmates being punished still received an ‘adequate’ quantity of food, indicating that diet was sometimes being severely restricted at this time. The Andover workhouse incident of 1845, where inmates were found gnawing on decayed animal bones due to the lack of food provided, was a national scandal, and a contributing factor in the replacement of the Poor Law Commission with the Poor Law Board in 1847.

Changes in attitudes towards diet and nutrition did arise during the Victorian period, largely due to the ‘Hungry Forties’. In addition to economic depression, this period saw crop failure in England, Scotland, and Ireland – most notably the horrors of An Gorta Mór (The Great Hunger) in Ireland. The suffering experienced prompted research into nutrition, broadening public understanding of the importance of the food they consumed, and altering what was considered an ‘adequate’ diet. This is not to say that workhouse diets saw drastic (or in some cases, any) improvement but as Ian Miller argues:

[if we] wish to recast Poor Law dietary provisions as scientifically 'adequate”', then this could be more convincingly achieved… from the 1860s onward.

Further reading

Find out more about the history of the workhouses in London in, 'Workhouses of London and the South East' by Peter Higginbotham (20.6 HIG) which is available in our reference library.

Explore the Lost Victorian CitySearch the London Picture Archive